The notion of Dravidian, it’s been already said, is defined linguistically: the Dravidian linguistic family occupies the major part of the Deccan peninsula, it unites several languages that are strongly correlated through their different features and forms a group that is clearly differentiated from other known linguistic families.

Anthropologists determined in the 19th century that this linguistic family coincides largely with a physical type, characterized by a very dark skin, a medium height (1.62 meters among the Tamils) and features that are closer to the Europeans than to the Veddah group: thinner nose, non-eversion of the lips, curly hair, dolichocephalic head but of a less pronounced degree, chin and forehead are not receding. This type is called Melano-Indian by Henri Vallois, who makes it one of the four great races of India.

Classical anthropology hesitated on their affiliation: if one goes by skin-color, the Melano-Indians are affiliated to the Blacks—this was the opinion, writes Vallois, of the majority of the authors—; if one sticks to other characteristics, they become closer, on the contrary, to the Europeans. “If it were not for their skin-color, [<p.45-46>] they could be taken for Europeans.” And more precisely, they belong, through all their traits, except color, to the vast Mediterranean group.

The coincidence between speakers of the Dravidian languages and the Melano-Indian type is ample, but it is no way perfect. The Melano-Indians form the basis of the Deccan population, but in the Gangetic plain and the north of the Deccan, millions of speakers of the Indo-Aryan languages are of the same type, whereas the Brahui, speakers of a Dravidian language of Pakistan, are distinguishable neither physically nor genetically from their Baluch, that is, Iranian neighbors. Finally, according to Vallois, “in two regions,” these Melano-Indians “are particularly pure”: on the one hand, in the Tamil country and, on the other hand, in “a large group that occupies the last foothills of the plateau up to the Gangetic plain: these are the Mundas and some other peoples. Now, the Mundas do not speak a Dravidian language but one with Far-Eastern affinities. It must be presumed that the earliest speakers of Munda languages were of the physical type seen among their Mon-Khmer linguistic cousins, that they were therefore of the ‘yellow’ race or, to use the anthropological terminology, mongoloids or xanthoderms. This speaks for the extent of population admixture.

It remains that the hypothesis that there may have been in the past a greater coincidence between Dravidian languages and Melano-Indian type carries weight: beyond the very large equivalence in the Deccan, it is known that the Dravidian languages retreated in the north before the Indo-Aryan languages: that is to say that the Melano-Indians who were of the Dravidian language two or three thousand years ago speak Indo-Aryan languages today. Inversely, the language and physical aspect of the Brahui is explicable through an opposite phenomenon: these Brahui have arrived in Pakistan during the Muslim epoch, towards the 13th century, and must have constituted an exclusively masculine military group that was relatively not numerous. They have taken women at their new location even while preserving their language—while persianizing their vocabulary with Iranian words—, and the properly Melano-Indian contribution ended up increasingly diluted in their intermarriages with the surrounding white populations. In both cases, it is easy to discern an earlier situation where, disregarding the Veddah substrate, the Deccan was a land that was both Dravidian from a linguistic point of view and Melano-Indian from an anthropological point of view. Thus there is a large coincidence between the two terms.

As we have seen, this Dravidian and Melano-Indian population has in fact been superimposed on an earlier veddhoid people with which it became mixed. Moreover, multivaried craniometric measurements [<p.46-47>] have revealed that the veddhoids, Dravidians (or, more exactly, Melano-Indians) and Mediterraneans are populations that are anthropologically very close, and represent three ‘waves’ of the same human ‘current’ issuing from Africa probably starting from the upper paleolithic. It has been emphasized how the prehistoric skulls of India and the neighboring countries to the north-west are often half-‘veddhoid’ or half-‘australoid’, depending on the authors, and half-‘dravidian’, which some interpret in terms of admixture, but which also bears testimony just as much to the affinity, the continuity of the two human layers under discussion. In turn, the succeeding human layer, that which brings into India the properly mediterranean type, in its variant labeled ‘indo-afghan’, is also their prolongation.

The Melano-Indians are thus ‘black Mediterraneans’. This can have three distinct explanations:

- either the original Homo sapiens sapiens population was dark, as is thought by many authors today, and in this case the white (leucoderm) and yellow (xanthoderm) ‘races’ result from depigmentation. In these conditions, one of two things is possible: either the Melano-Indians evidence a primitive state, still pigmented, of the mediterranean type, or instead, since all other Mediterraneans, in their numerous anthropological variants (called ibero-insular, atlanto-mediterranean, indo-afghan, south-oriental, saharan, nordic), are white, the Melano-Indians owe their color to a process of repigmentation in the tropical zone over the millennia;

- or the Melano-Indians/Dravidians, few in number on their arrival in India, have mixed with the previous, itself pigmented, veddhoid population, and it is this anthropological ‘substrate’ which is at the origin of their color.

Now, if we recall that the resemblances among Nubians, proto-dynastic Egyptians, Dravidians and what was formerly called “Hamites” appear henceforth through multivaried cranial measurements “as being very evident,” and that among the so-called “Hamites” (in reality of the kushitic languages, that is to say the linguistic family called semito-hamite), the Somalis and Galla are black-skinned, it is probable that the Dravidians have conserved their color on leaving Africa; their installation in the Indian tropical zone could have subsequently only confirmed and augmented this pigmentationhttp://www.svabhinava.org/aitvsoit/Sergent-AfroDravidian-frame.php

Traditional South Indian clothing potrayed here in an oil painting!!!

Traditional South Indian clothing potrayed here in an oil painting!!!

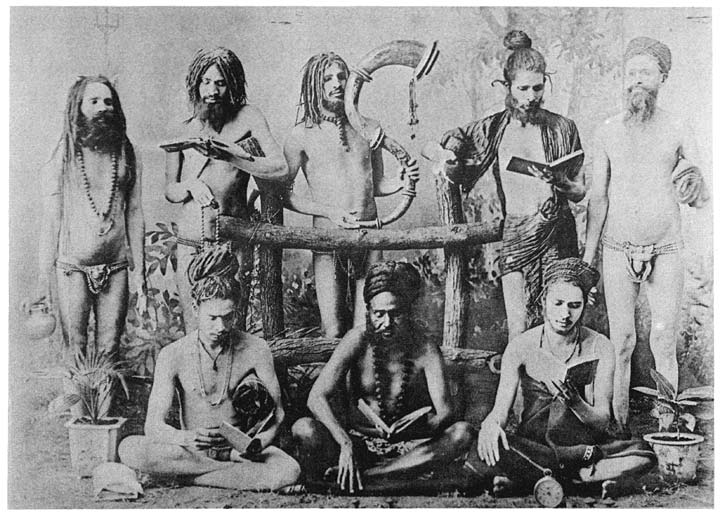

DRAVIDIAN YOGI ASCETICS WITH DREADLOCKS ;(like Rasta in Jamaica) CENTRAL INDIA

DRAVIDIAN YOGI ASCETICS WITH DREADLOCKS ;(like Rasta in Jamaica) CENTRAL INDIA